Developing a new video conferencing application often begins with a peer-to-peer setup using WebRTC, facilitating direct data exchange between clients. While effective for small demonstrations, this method encounters scalability hurdles with increased participants. The data transmission load for each client escalates significantly in proportion to the number of users, as each client is required to send data to every other client except themselves (n-1).

In the scaling of video conferencing applications, Selective Forwarding Units (SFUs) are essential. Essentially a media stream routing hub, an SFU receives media and data flows from participants and intelligently determines which streams to forward. By strategically distributing media based on network conditions and participant needs, this mechanism minimizes bandwidth usage and greatly enhances scalability. Nearly every video conferencing application today uses SFUs.

In 2024, we announced Cloudflare Realtime (then called Cloudflare Calls), our suite of WebRTC products, and we also released Orange Meets, an open source video chat application built on top of our SFU.

We also realized that use of an SFU often comes with a privacy cost, as there is now a centralized hub that could see and listen to all the media contents, even though its sole job is to forward media bytes between clients as a data plane.

We believe end-to-end encryption should be the industry standard for secure communication and that’s why today we’re excited to share that we’ve implemented and open sourced end-to-end encryption in Orange Meets. Our generic implementation is client-only, so it can be used with any WebRTC infrastructure. Finally, our new designated committer distributed algorithm is verified in a bounded model checker to verify this algorithm handles edge cases gracefully.

End-to-end encryption describes a secure communication channel whereby only the intended participants can read, see, or listen to the contents of the conversation, not anybody else. WhatsApp and iMessage, for example, are end-to-end-encrypted, which means that the companies that operate those apps or any other infrastructure can’t see the contents of your messages.

Whereas encrypted group chats are usually long-lived, highly asynchronous, and low bandwidth sessions, video and audio calls are short-lived, highly synchronous, and require high bandwidth. This difference comes with plenty of interesting tradeoffs, which influenced the design of our system.

We had to consider how factors like the ephemeral nature of calls, compared to the persistent nature of group text messages, also influenced the way we designed E2EE for Orange Meets. In chat messages, users must be able to decrypt messages sent to them while they were offline (e.g. while taking a flight). This is not a problem for real-time communication.

The bandwidth limitations around audio/video communication and the use of an SFU prevented us from using some of the E2EE technologies already available for text messages. Apple’s iMessage, for example, encrypts a message N-1 times for an N-user group chat. We can’t encrypt the video for each recipient, as that could saturate the upload capacity of Internet connections as well as slow down the client. Media has to be encrypted once and decrypted by each client while preserving secrecy around only the current participants of the call.

Around the same time we were working on Orange Meets, we saw a lot of excitement around new apps being built with Messaging Layer Security (MLS), an IETF-standardized protocol that describes how you can do a group key exchange in order to establish end-to-end-encryption for group communication.

Previously, the only way to achieve these properties was to essentially run your own fork of the Signal protocol, which itself is more of a living protocol than a solidified standard. Since MLS is standardized, we’ve now seen multiple high-quality implementations appear, and we’re able to use them to achieve Signal-level security with far less effort.

Implementing MLS here wasn’t easy: it required a moderate amount of client modification, and the development and verification of an encrypted room-joining protocol. Nonetheless, we’re excited to be pioneering a standards-based approach that any customer can run on our network, and to share more details about how our implementation works.

We did not have to make any changes to the SFU to get end-to-end encryption working. Cloudflare’s SFU doesn’t care about the contents of the data forwarded on our data plane and whether it’s encrypted or not.

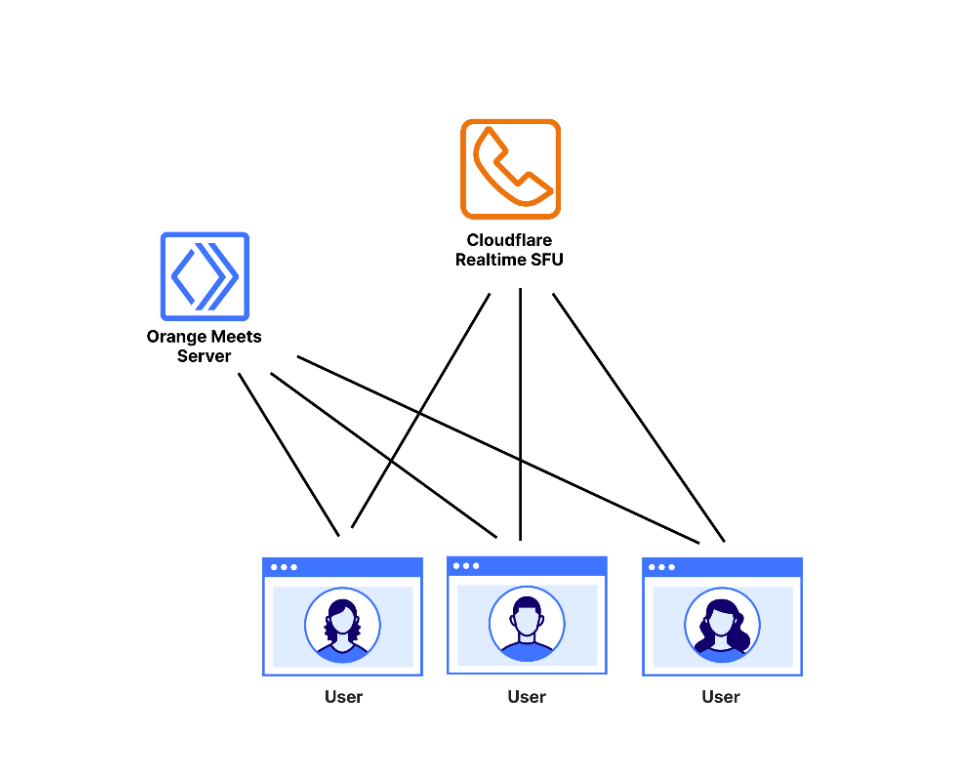

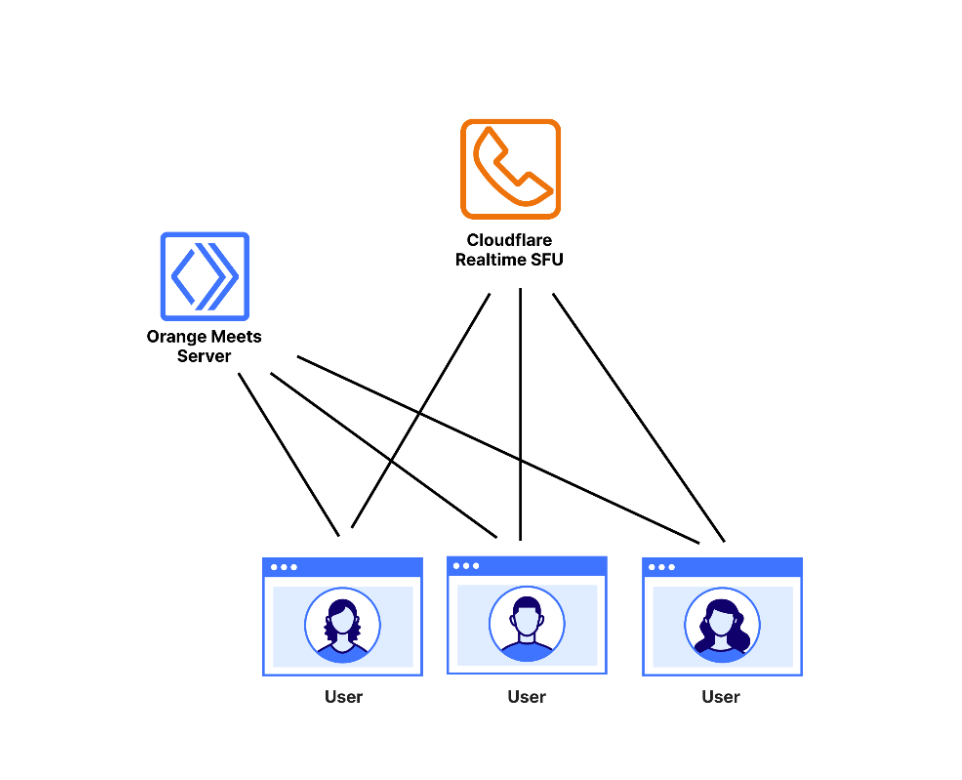

Orange Meets is a video calling application built on Cloudflare Workers that uses the Cloudflare Realtime SFU service as the data plane. The roles played by the three main entities in the application are as follows:

-

The user is a participant in the video call. They connect to the Orange Meets server and SFU, described below.

-

The Orange Meets Server is a simple service run on a Cloudflare Worker that runs the small-scale coordination logic of Orange Meets, which is concerned with which user is in which video call — called a room — and what the state of the room is. Whenever something in the room changes, like a participant joining or leaving, or someone muting themselves, the app server broadcasts the change to all room participants. You can use any backend server for this component, we just chose Cloudflare Workers for its convenience.

-

Cloudflare Realtime Selective Forwarding Unit (SFU) is a service that Cloudflare runs, which takes everyone’s audio and video and broadcasts it to everyone else. These connections are potentially lossy, using UDP for transmission. This is done because a dropped video frame from five seconds ago is not very important in the context of a video call, and so should not be re-sent, as it would be in a TCP connection.

The network topology of Orange Meets

Next, we have to define what we mean by end-to-end encryption in the context of video chat.

The most immediate way to end-to-end encrypt Orange Meets is to simply have the initial users agree on a symmetric encryption/decryption key at the beginning of a call, and just encrypt every video frame using that key. This is sufficient to hide calls from Cloudflare’s SFU. Some source-encrypted video conferencing implementations, such as Jitsi Meet, work this way.

The issue, however, is that kicking a malicious user from a call does not invalidate their key, since the keys are negotiated just once. A joining user learns the key that was used to encrypt video from before they joined. These failures are more formally referred to as failures of post-compromise security and perfect forward secrecy. When a protocol successfully implements these in a group setting, we call the protocol a continuous group key agreement protocol.

Fortunately for us, MLS is a continuous group key agreement protocol that works out of the box, and the nice folks at Phoenix R&D and Cryspen have a well-documented open-source Rust implementation of most of the MLS protocol.

All we needed to do was write an MLS client and compile it to WASM, so we could decrypt video streams in-browser. We’re using WASM since that’s one way of running Rust code in the browser. If you’re running a video conferencing application on a desktop or mobile native environment, there are other MLS implementations in your preferred programming language.

Our setup for encryption is as follows:

Make a web worker for encryption. We wrote a web worker in Rust that accepts a WebRTC video stream, broken into individual frames, and encrypts each frame. This code is quite simple, as it’s just an MLS encryption:

group.create_message(

&self.mls_provider,

self.my_signing_keys.as_ref()?,

frame,

)Postprocess outgoing audio/video. We take our normal stream and, using some newer features of the WebRTC API, add a transform step to it. This transform step simply sends the stream to the worker:

const senderStreams = sender.createEncodedStreams()

const { readable, writable } = senderStreams

this.worker.postMessage(

{

type: 'encryptStream',

in: readable,

out: writable,

},

[readable, writable]

)And the same for decryption:

const receiverStreams = receiver.createEncodedStreams()

const { readable, writable } = receiverStreams

this.worker.postMessage(

{

type: 'decryptStream',

in: readable,

out: writable,

},

[readable, writable]

)Once we do this for both audio and video streams, we’re done.

The streams are now encrypted before sending and decrypted before rendering, but the browser doesn’t know this. To the browser, the stream is still an ordinary video or audio stream. This can cause errors to occur in the browser’s depacketizing logic, which expects to see certain bytes in certain places, depending on the codec. This results in some extremely cypherpunk artifacts every dozen seconds or so:

Fortunately, this exact issue was discovered by engineers at Discord, who handily documented it in their DAVE E2EE videocalling protocol. For the VP8 codec, which we use by default, the solution is simple: split off the first 1–10 bytes of each packet, and send them unencrypted:

fn split_vp8_header(frame: &[u8]) -> Option<(&[u8], &[u8])> {

// If this is a keyframe, keep 10 bytes unencrypted. Otherwise, 1 is enough

let is_keyframe = frame[0] >> 7 == 0;

let unencrypted_prefix_size = if is_keyframe { 10 } else { 1 };

frame.split_at_checked(unencrypted_prefix_size)

}These bytes are not particularly important to encrypt, since they only contain versioning info, whether or not this frame is a keyframe, some constants, and the width and height of the video.

And that’s truly it for the stream encryption part! The only thing remaining is to figure out how we will let new users join a room.

Usually, the only way to join the call is to click a link. And since the protocol is encrypted, a joining user needs to have some cryptographic information in order to decrypt any messages. How do they receive this information, though? There are a few options.

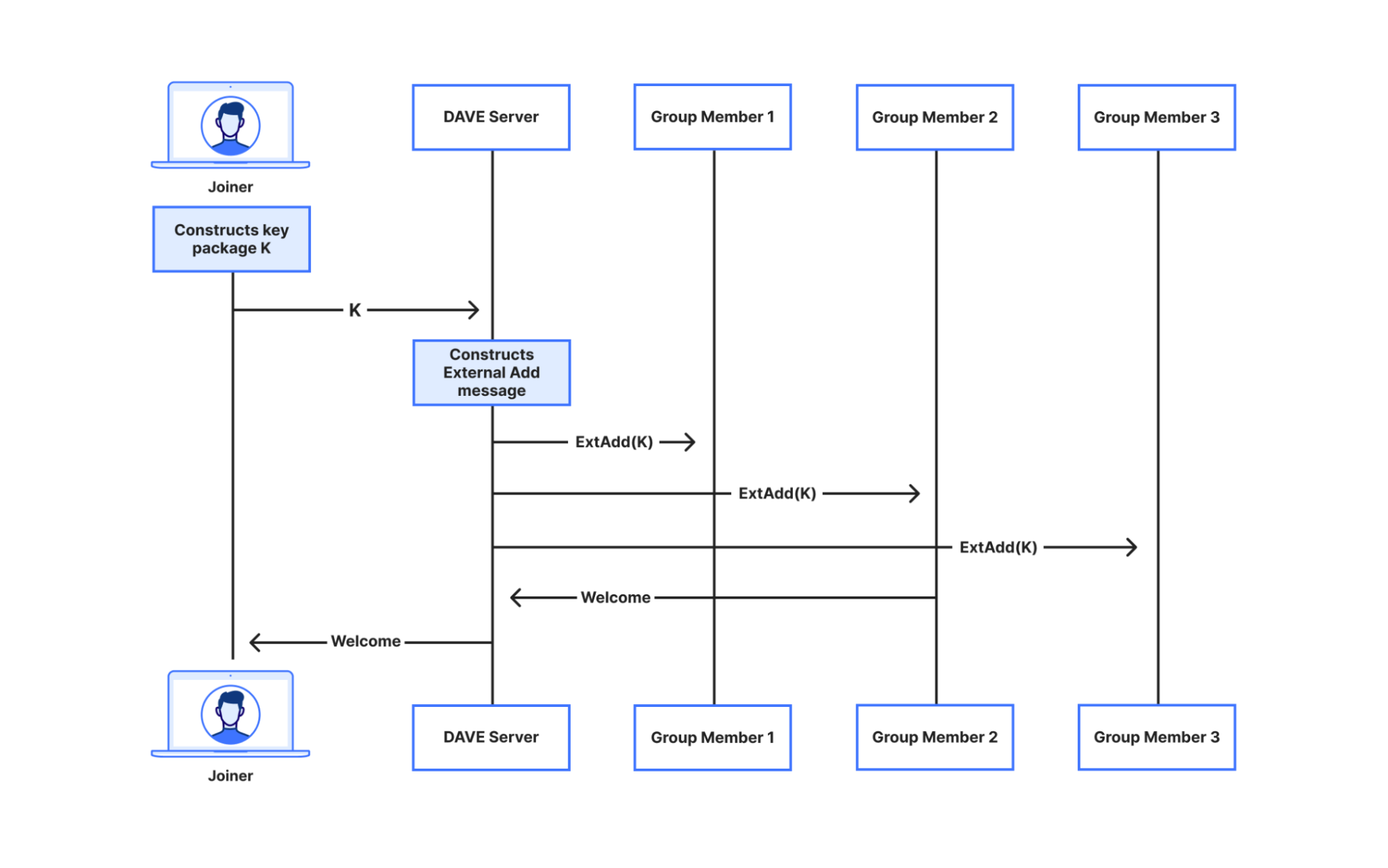

DAVE does it by using an MLS feature called external proposals. In short, the Discord server registers itself as an external sender, i.e., a party that can send administrative messages to the group, but cannot receive any. When a user wants to join a room, they provide their own cryptographic material, called a key package, and the server constructs and sends an MLS External Add message to the group to let them know about the new user joining. Eventually, a group member will commit this External Add, sending the joiner a Welcome message containing all information necessary to send and receive video.

A user joining a group via MLS external proposals. Recall the Orange Meets app server functions as a broadcast channel for the whole group. We consider a group of 3 members. We write member #2 as the one committing to the proposal, but this can be done by any member. Member #2 also sends a Commit message to the other members, but we omit this for space.

This is a perfectly viable way to implement room joining, but implementing it would require us to extend the Orange Meets server logic to have some concept of MLS. Since part of our goal is to keep things as simple as possible, we would like to do all our cryptography client-side.

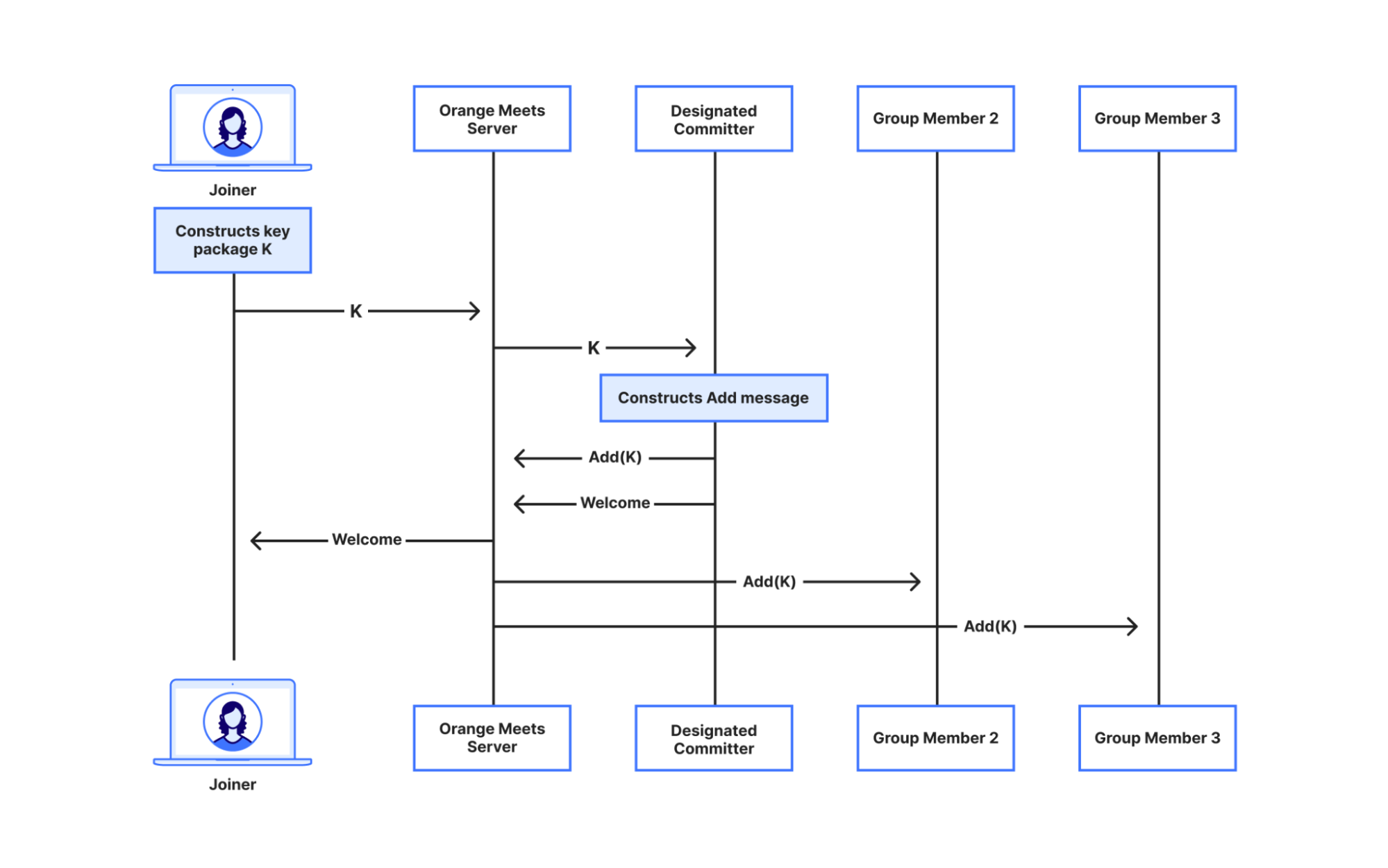

So instead we do what we call the designated committer algorithm. When a user joins a group, they send their cryptographic material to one group member, the designated committer, who then constructs and sends the Add message to the rest of the group. Similarly, when notified of a user’s exit, the designated committer constructs and sends a Remove message to the rest of the group. With this setup, the server’s job remains nothing more than broadcasting messages! It’s quite simple too—the full implementation of the designated committer state machine comes out to 300 lines of Rust, including the MLS boilerplate, and it’s about as efficient.

A user joining a group via the designated committer algorithm.

One cool property of the designated committer algorithm is that something like this isn’t possible in a text group chat setting, since any given user (in particular, the designated committer) may be offline for an arbitrary period of time. Our method works because it leverages the fact that video calls are an inherently synchronous medium.

The designated committer algorithm is a pretty neat simplification, but it comes with some non-trivial edge cases that we need to make sure we handle, such as:

-

How do we make sure there is only one designated committer at a time? The designated committer is the alive user with the smallest index in the MLS group state, which all users share.

-

What happens if the designated committer exits? Then the next user will take its place. Every user keeps track of pending Adds and Removes, so it can continue where the previous designated committer left off.

-

If a user has not caught up to all messages, could they think they’re the designated committer? No, they have to believe first that all prior eligible designated committers are disconnected.

To make extra sure that this algorithm was correct, we formally modeled it and put it through the TLA+ model checker. To our surprise, it caught some low-level bugs! In particular, it found that, if the designated committer dies while adding a user, the protocol does not recover. We fixed these by breaking up MLS operations and enforcing a strict ordering on messages locally (e.g., a Welcome is always sent before its corresponding Add).

You can find an explainer, lessons learned, and the full PlusCal program (a high-level language that compiles to TLA+) here. The caveat, as with any use of a bounded model checker, is that the checking is, well, bounded. We verified that no invalid protocol states are possible in a group of up to five users. We think this is good evidence that the protocol is correct for an arbitrary number of users. Because there are only two distinct roles in the protocol (designated committer and other group member), any weird behavior ought to be reproducible with two or three users, max.

One important concern to address in any end-to-end encryption setup is how to prevent the service provider from replacing users’ key packages with their own. If the Orange Meets app server did this, and colluded with a malicious SFU to decrypt and re-encrypt video frames on the fly, then the SFU could see all the video sent through the network, and nobody would know.

To resolve this, like DAVE, we include a safety number in the corner of the screen for all calls. This number uniquely represents the cryptographic state of the group. If you check out-of-band (e.g., in a Signal group chat) that everyone agrees on the safety number, then you can be sure nobody’s key material has been secretly replaced.

In fact, you could also read the safety number aloud in the video call itself, but doing this is not provably secure. Reading a safety number aloud is an in-band verification mechanism, i.e., one where a party authenticates a channel within that channel. If a malicious app server colluding with a malicious SFU were able to construct believable video and audio of the user reading the safety number aloud, it could bypass this safety mechanism. So if your threat model includes adversaries that are able to break into a Worker and Cloudflare’s SFU, and simultaneously generate real-time deep-fakes, you should use out-of-band verification 😄.

There are some areas we could improve on:

-

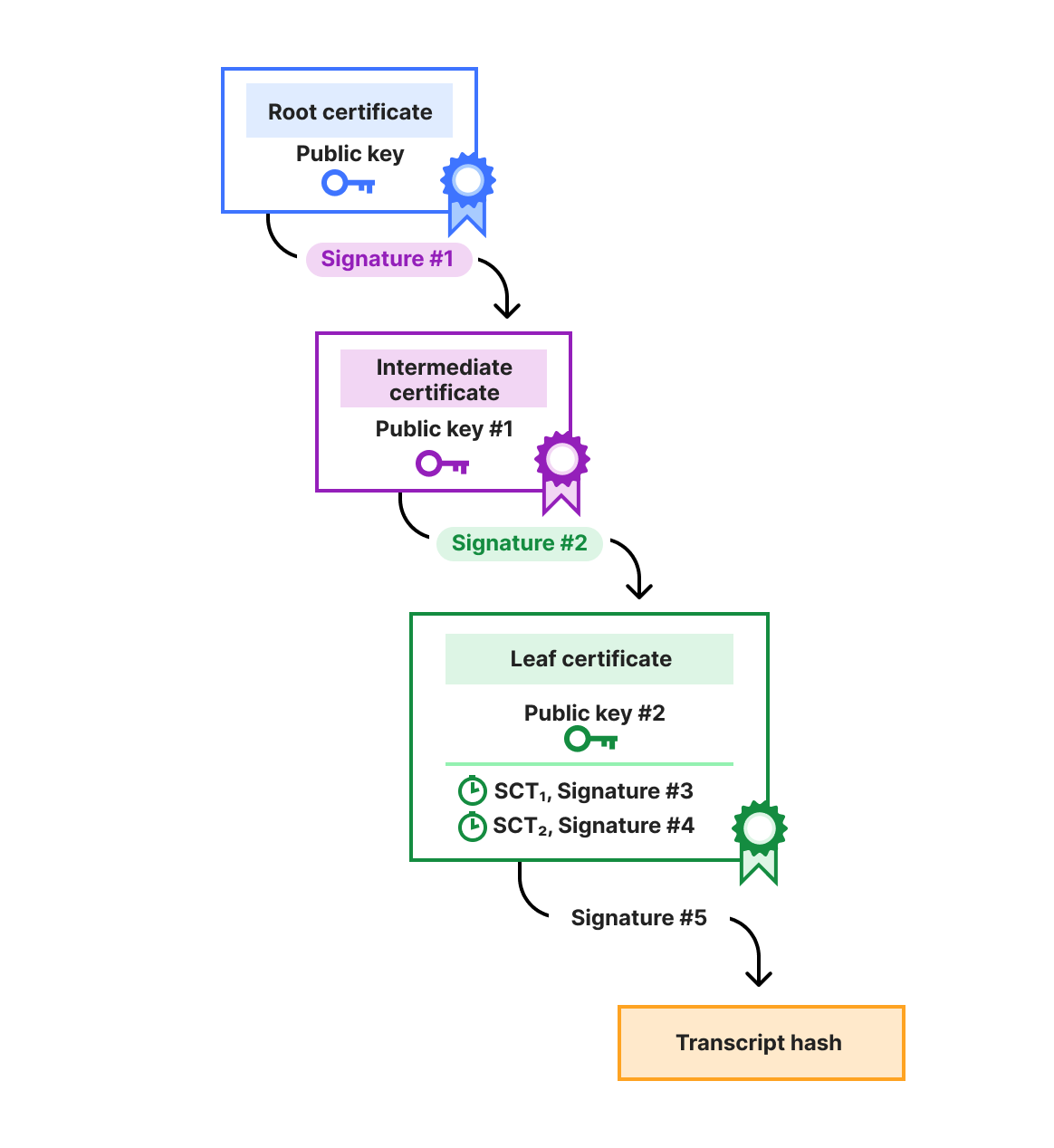

There is another attack vector for a malicious app server: it is possible to simply serve users malicious Javascript. This problem, more generally called the Javascript Cryptography Problem, affects any in-browser application where the client wants to hide data from the server. Fortunately, we are working on a standard to address this, called Web Application Manifest Consistency, Integrity, and Transparency. In short, like our Code Verify solution for WhatsApp, this would allow every website to commit to the Javascript it serves, and have a third party create an auditable log of the code. With transparency, malicious Javascript can still be distributed, but at least now there is a log that records the code.

-

We can make out-of-band authentication easier by placing trust in an identity provider. Using OpenPubkey, it would be possible for a user to get the identity provider to sign their cryptographic material, and then present that. Then all the users would check the signature before using the material. Transparency would also help here to ensure no signatures were made in secret.

We built end-to-end encryption into the Orange Meets video chat app without a lot of engineering time, and by modifying just the client code. To do so, we built a WASM (compiled from Rust) service worker that sets up an MLS group and does stream encryption and decryption, and designed a new joining protocol for groups, called the designated committer algorithm, and formally modeled it in TLA+. We made comments for all kinds of optimizations that are left to do, so please send us a PR if you’re so inclined!

Try using Orange Meets with E2EE enabled at e2ee.orange.cloudflare.dev, or deploy your own instance using the open source repository on Github.